Computer-aided Patient Scheduling

Without a computerized scheduler, a practice has less than a 2% chance of earning the title of a “better-performing practice,” according to the Medical Group Management Association. Computerized scheduling helps decrease service costs, provide fairness in service delivery, increase patient satisfaction, and reduce waiting times (Zhang et al., 2019). A massive investment in scheduling features across a wide spectrum of billing products indicates the importance of computerized scheduling. Convenience and front office efficiencies are two obvious benefits of a computerized scheduling system; without them, the only manual way to find out if a specific patient has a scheduled appointment is to flip through the appointment book page by page. Worse, manual scheduling hurts both patient satisfaction and practice financial performance because of scheduling inconsistencies and unbilled (and therefore unpaid) visits. But the benefits of integrated computerized scheduling stretch far beyond convenience, front office efficiencies, and better charge follow-up of stand-alone, albeit computerized, scheduling. A well-designed and integrated scheduler allows preferential patient scheduling, which, along with improved controls, helps revenue optimization and practice compliance. Next, we review key aspects of computerized scheduling and demonstrate the important benefits of integrated scheduling, billing, and compliance management. Scheduling Policies Computerized schedulers allow a combination of single- or multiple-interval scheduling, with open-access scheduling subject to various priority constraints. Such priority-constraint-driven, open-access scheduling creates preferential appointments based on patient demographics or insurance coverage. Typical time-slot-based appointment systems essentially divide a physician’s schedule into finite slots in a day, which can be allocated according to appointment requests. However, such systems are limited by the risks of schedule fragmentations in late shows or no-shows (Chen et al., 2019). Examples of time-slots-based scheduling include single-interval scheduling and multiple-interval scheduling. Single-interval scheduling allocates appointments at regular intervals of 5 to 15 minutes, depending on the specialty. The downside of single-interval scheduling is that as soon as one appointment takes longer than the allocated slot, all subsequent patients must wait. Multiple-interval scheduling also sets appointments at regular intervals; however, unlike single-interval scheduling, it allocates the appointment length depending on the chief complaint. Such scheduling requires up-front categorization of key appointment types and their projected lengths. For instance, an initial appointment might take 30 minutes, while a routine injection might take only 5 minutes. According to the CAHPS survey database, about 12% of patients who called in did not get appointments for urgent care that they needed at the time. Forjuo et al., (2001) also showed that inadequate access to primary care providers was a leading cause of patient dissatisfaction. These challenges are mitigated by open-access scheduling. Open-access scheduling requires holding several appointments open every day. These open appointments are filled only within 48 hours of the appointment, catering to same-day or last-minute patient requests. Open-access scheduling improves access to the physician, reduces no-shows, and eliminates patient screening time. The downside of open-access scheduling is, of course, the potential for longer patient waiting lines or physician idle time because of the inability to maintain a predictable patient flow. A novel scheduling variant is the overlapping appointment scheduling (OLAS) model (Huet et al., 2020). OLAS model refers to deciding the optimal overlapping periods between the patient appointment and allocated service times. The model is formulated as an optimization problem to minimize the total cost of patients waiting and doctors’ idle time. One way to balance the practice workload is to schedule group, routine, or repeat appointments during slow hours. For instance, pediatric well-child visits or patients with a particular chronic disease—such as congestive heart failure or diabetes—could be scheduled for early mornings when there are typically fewer patients waiting in line. These scheduled visits include educational components and often involve multidisciplinary teams. It also helps save time since standard advice need not be repeated to individuals, improving on the efficiency of care delivery (Jones et al., 2019). Patients also benefit from the socialization aspect of group visits; members encourage one another, exercise together, and so forth. A good scheduler allows a repeat appointment schedule subject to total frequency and time slot constraints. Compliance Process An integrated scheduler verifies the filing of a signed patient consent form—and, in certain cases, a signed ABN form. An ABN (Advance Beneficiary Notice) serves three goals: To protect the beneficiaries from liability for services denied as not reasonable (depends on the frequency or duration) and necessary (depends on the diagnosis and the provider’s specialty) To protect the provider’s revenue by shifting financial liability for denied services to the patient To provide documentation for a Medicare audit For more complex procedures, the scheduler warns the front office about the need to obtain all required diagnostic test results and clearances up front. Billing Interface The integrated scheduler avoids unbillable patient encounters and reconciles visits with patient balances. It checks outstanding patient balances and verifies coverage and eligibility at the point of scheduling before the appointment. AI-driven computerized coding and billing systems can accurately provide the code for a particular disease condition and help with appropriate automated billing (Venkatesh et al., 2023). In many cases, such a test discovers data entry errors too, reducing the payment cycle at later stages. Additionally, the insurance company may require referrals or separate pre-authorization/certification for certain procedures, refusing the payment if the procedure was performed without a referral or preauthorization. The integrated scheduler can access medical records to supply necessary background and diagnosis information to obtain pre-authorization. Finally, without the ability to reconcile visits with payments, the practice owner cannot be sure that every visit resulted in a payment. Practice Flow Interface The integrated scheduler manages the entire patient flow, continuously updating arrival lists, checkoffs, and office/room tracking. Further, the scheduler tracks no-shows and follow-up actions. Detailed reports include daily schedules, load reports, missed appointments, free time, canceled appointments, etc. With AI-integrated schedulers, different color codes and status flags can be used for different appointment types, whether emergencies or routine or based on the specialist to be seen by the patient. This offers a good visually appealing summary by just glancing over the

Value Adding for Maximum Profit

I love this topic because it’s easy to miss the mark, especially since so many consultants and marketing firms misappropriate this term and don’t actually coach on value-adding. The idea of value-adding has come under scrutiny in light of the current trend of corporate acquisitions of primary care clinics and the rising patient expectation for comprehensive, patient-centered treatment (Abelson, 2023). This is because of how the healthcare industry is changing. There is a growing need to separate actual value addition from empty rhetoric when corporate companies acquire primary care operations. The demand for genuine, efficient value-adding solutions has never been greater due to the rise in patient expectations for a comprehensive healthcare experience. Don’t get me wrong, plenty do an absolutely amazing job, and their clients see great results, but more often than not, disaster strikes. Especially in the case of Joseph and Bonnie… When Joseph and Bonnie opened their practice, they were die-hard, convinced that they only needed to practice their specialty and nothing else. If we stay true to our specialty’s expertise and principles, we shouldn’t need anything else in the practice to thrive. Although reasonable, this viewpoint failed to consider the changing expectations of healthcare consumers. Patients are increasingly looking for holistic healthcare that covers their current requirements and their long-term well-being, according to Yussof et al. (2022). This suggests Joseph and Bonnie’s single-focused strategy didn’t meet the patient’s desire for comprehensive care. Today’s patients want treatments that address their current health needs and promote wellness, including preventative and long-term health management. Thus, healthcare professionals who offer more services are valued more. So they went about building out a space with the money their mentor had given them and whatever they could find and were adamant that physical therapy was the only service to be offered. Once the space was open, they began marketing to orthopedists in the area and getting patient referrals. That’s when the opportunities opened up. Patients started asking about ancillary services they didn’t have, making them feel like they looked silly. Patients asked about home fitness programs, nutrition, supplementation, and other specialties like Chiropractic or group fitness. The study by Patel & Singhal (2023) demonstrates the growing tendency of patients to seek comprehensive care. It showed that most patients favor healthcare facilities that offer various services under one roof. Patients increasingly view healthcare as a holistic activity. They want nutrition advice, exercise regimens, and alternative cures, not just specialist therapy. This shift in patient preferences fuels the desire for multi-service healthcare facilities that can meet several health and wellness goals. Initially, Joseph and Bonnie ignored it and kept progressing, growing at around 10%. They did a first-quarter review, and it was clear they were not on track to meet their financial freedom goals. They were convinced that something had to change, but they knew working harder to build new referring relationships was not scalable. They could only see so many patients daily, and hiring more therapists would add to their overhead. They needed a solution that minimized overhead growth while maximizing potential revenue. Joseph and Bonnie started taking patient requests seriously and realized a clear pattern. Patients were looking for wellness, not just treatment. Patients wanted to know if they could have a one-stop shop for preventative and therapeutic care. This was a new concept to Joseph and Bonnie, but they began exploring it and found an incredible and vast potential revenue stream in things like product offerings, DME, and more. Such a change toward integrated healthcare delivery is consistent with the ongoing tendency within the pharmaceutical sector to develop into wellness providers with patient-centric services (Moreno, 2019). This represents a larger healthcare shift from treating sickness to promoting well-being. Pharmaceutical corporations are expanding their position to include disease prevention, wellness, and patient-centric services for different health needs. Patients want a single source of preventative and therapeutic care. At first, Joseph and Bonnie only wanted to add what they could manage and keep the specialty singular. However, it soon became clear that their patients were looking for a more sophisticated preventative care so they hired a part-time nutritionist who turned into a full-time nutritionist. They bought used fitness equipment and hired a part-time fitness instructor who turned into a full-time instructor (Joseph recently replaced this person as the full-time trainer because of his personal love of fitness; the perks of being the boss). So what is value adding? Is it simply the addition of multiple complementary specialties into your practice? Maybe. Recent developments in primary and pharmacy care have demonstrated that value addition can be achieved by implementing cutting-edge health methods like digital medicines and remote patient monitoring (Smith, 2021). Value-adding extends beyond incorporating diverse specialties. Digital medicines and remote patient monitoring improve patient care and convenience. These strategies satisfy patients’ desire for individualized, accessible treatment, bringing value to a practice. It could also be the addition of community events, marble floors in the patient bathroom, or a cooling station with fancy refreshments. The true value add in a practice is unique to the patient community. It’s a matter of listening to the value-adds they seek and finding a way to accommodate them that supports the larger purpose and mission. If your practice is in a really nice part of town and you managed to get a great deal on space but are short on cash, it could be a matter of setting up one fancy area in your practice that you can afford to spruce up (it should also be functional, before you go replacing drapes). Whatever change you attempt needs to address two things: Patient requests – Surveys often help the most in this area Patient function – You want the value to add(s) to be usable in some way that improves the patient’s experience both individually and as a group A fancy cooling station with multiple settings, fruit, vegetable-enhanced water, and more can get patients talking and feeling fancy. Often these changes can also help enhance the practice’s

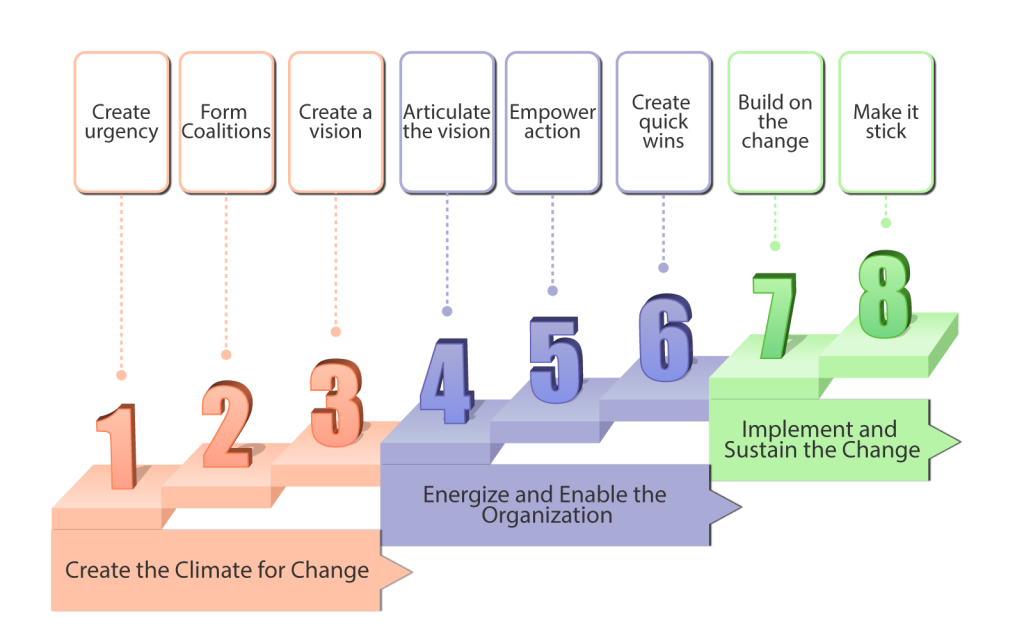

Change Management – Switching Your Billing Systems

Practice owners seeking better solutions often start with a vision of increased practice profitability while treating reasonable patient volumes. Their vision spans multiple aspects, including better reach to prospective patients, better reimbursement rates, full and timely payments by insurance companies, less time spent on visit documentation, improved documentation quality for better clinical follow-up and lower audit risk, and more free time for family. However, that vision conflicts directly with the payers’ goals to reduce costs and increase revenues. Payers’ goals directly conflict with a provider’s vision because cost savings for payers simply mean that providers treat more patients at lower reimbursement rates—or, in other words, providers work harder for less money. In addition to the basic payer-provider conflict, visionary practice owners must face the resistance of their office managers and colleagues. These people may be skeptical because they don’t trust the owner, have seen five other failed initiatives, or think they might lose something with the change. Significant time, enthusiasm, and resources are needed to change practice processes and technology and to retrain personnel while simultaneously managing the practice and treating patients. The challenge of overcoming resistance to change and implementing it in your practice is akin to enhancing airplane engineering while keeping the plane in the air. Thus, medical practice owners often find themselves in a dilemma between adopting new solutions or compromising the vision and returning to the old ways, along with shrinking revenues and growing frustration. One key area of medical practice that requires a huge transition is shifting from paper-based records to an electronic health record (EHR) system. Shifting from one EHR system to another is also burdensome and requires a systematic approach to achieve results. Several internet-based software and tools can aid medical practices in transitioning to electronic records successfully, leading to maximized outputs and better service delivery to patients. We shall look at how to adopt this change using a change model. EHR and billing processes can help providers cut costs, improve the quality and safety of care, and enhance the productivity of the employees. Most practices have adopted EHR and electronic billing systems to achieve the above goals, whereas some have stuck to using paper documentation and filing systems. Paper-based records are often tiresome to retrieve, prone to errors and misplacements in addition to being bulky and space-consuming to store. Paper-based billing systems have also been shown to take longer claims processing times than EHR due to the time taken to verify manually. To fully realize change and adopt it into practice, a stepwise approach has to be taken, failure to which frustrations and complacencies are bound to occur, leading to regression to previous ways. John Kotter, a Harvard Business School professor and the world’s foremost authority on leadership and change, discovered that transformation challenges span multiple industries and share the same characteristics. His book Leading Change lists an eight-step process for implementing successful transformations. The eight steps can be divided into 3 phases: creating the climate for change, energizing & enabling them, and implementing and sustaining the change (National Learning Consortium, 2013). The figure below illustrates these three phases. Figure 1: The three phases of Kotter’s eight-step change management model This model has successfully been used to help transition into an electronic health records system in clinical practices. For instance, North Shore Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois, successfully transitioned from 100 percent paper-based medical records to 100 percent electronic records in 2013 using Kotter’s eight-step model (Martin and Voynov, 2014). An orthopedic practice group in Ontario, Canada, also successfully transitioned from paper records to electronic records, achieving more than a 95% threshold using Kotter’s change model (Auguste, 2013). We shall look into the eight steps in detail using an example of a healthcare practice that desires to transition from paper-based records to electronic health records and billing. Step 1: Create a sense of urgency. In this step, a health practice can provide evidence to its employees on the need for an EHR. This can include faster claims processing, less bulky storage space, easy records retrieval, and better security. At this stage, the aim is for employees to buy into EHR and keep talking about the proposed change. Step 2: Form a powerful coalition. To help convince employees that change is necessary, the practice can develop a committee of committed and passionate individuals who constantly champion EHR. These individuals can work as a team to help identify barriers to implementation as well as help remind other employees of the need for EHR constantly. Step 3- Create a vision for change. The practice can develop a clear and concise vision through the committee, which motivates transition. An example of a vision would be establishing the most secure health records for clinic patients. Step 4: Communicate the vision for buy-in. Once the vision is created, it must be communicated to the employees clearly explaining the benefits to encourage buy-in. This can be achieved through face-to-face meetings, sending email reminders on the transition from paper to EHR, and individual interviews. Step 5: Remove obstacles. There are 5 categories of barriers hinder any change from occurring in an organization, the biggest of which are complacency and resistance to change (IvyPanda, 2020). The 5 categories include complacency, Limited sharing of the vision, Different obstacles to the vision, Inability to accomplish short-term wins, and failure to solidify the change in the practice culture. Let’s briefly talk about the five categories of barriers. 1. Complacency– This is the most deadly of practice change management problems. Suppose you just plunge ahead with a new electronic medical records (EMR) system or billing process without first establishing a shared sense of immediate need or urgency because of increased audit risk or shrinking revenue. In that case, natural complacency takes over—and the entire change effort fails. It’s hard to drive people out of their comfort zones. Past failures, the lack of a visible crisis, low-performance standards, and insufficient feedback from doctors, office personnel, and patients—all add up to turning the best-intended change initiatives

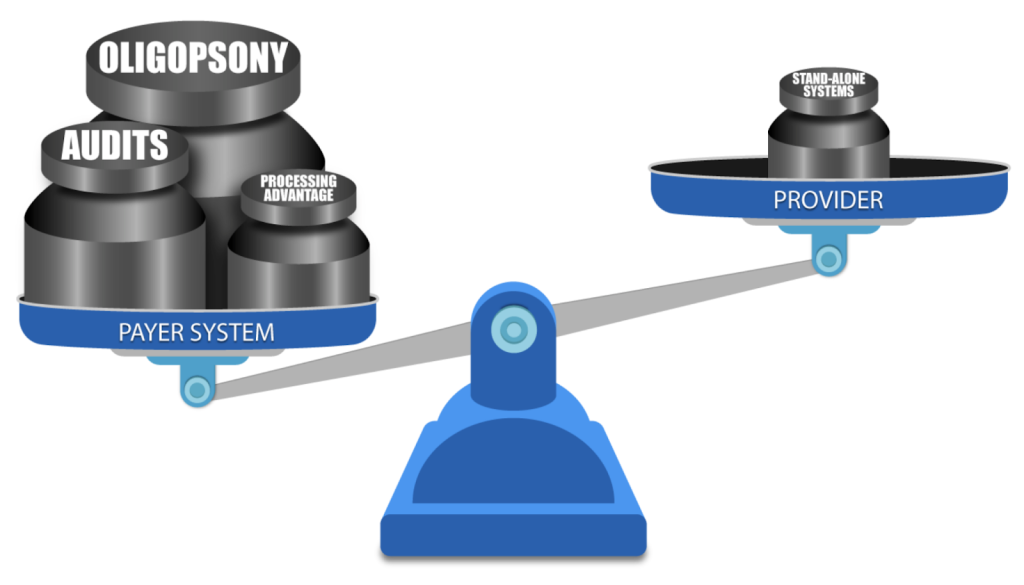

Why ClinicMind?

DO YOU know a practice owner who wants more patients in her clinic, better pay-per-visit, and better collections? We all know healthcare practice owners who want to remain independent and grow and yet are frustrated by insurance companies and continuous battles to get paid and stay compliant. Now, as a patient, do you like visiting a healthcare practice, receiving bills, and reconciling them with your insurance company? You are not alone. As it turns out, most other people do not like their patient experience. The problem is that patient and independent practice needs have evolved in step with society and technology, but management methodology remained in the 19th century. There’s a fundamental mismatch between how healthcare practices and patients are managed — and the practice owners’ and patients’ expectations. We came to a startling observation: patients no longer want their care to be managed the way it used to be managed in the previous century. And yet, practice owners still use their old methods to memory-manage their practice. Who is taking advantage of this mismatch? The insurance companies – payers. From the outset, we knew that healthcare costs are spiraling out of control. We also knew that insurance companies, medical equipment manufacturers, pharmaceuticals, and hospital executives have been all making handsome returns and benefitting from healthcare cost growth. One question bothered us: why are the practice owners unable to participate in that growth? How was it that the key contributors to healthcare service were excluded from fair compensation for their work and grew exceedingly frustrated with rules and regulations? Some providers were selling their practices to join larger networks or hospitals, and others were moving to different industries. National studies have shown that physician burnout rates are climbing up. For instance, Mayo Clinic Proceedings reported that the prevalence of burnout among U.S. physicians was 63% in 2021, compared with 38% in 2020, 44% in 2017, 54% in 2014, and 46% in 2011. We also noticed that with experience, medical billing managers start cherry-picking insurance companies for easy follow-up. So, the practice owners could not get paid on time and in full by a growing number of insurance companies (payers). The more obstacles payers pose – the less paid the providers are. Payers were stacking the game against the providers by continuously adding new rules to reduce payments and increasing the frequency of provider audits. In addition to continuous consolidation, resulting in scarcity of payers (a market structure known in economics as Oligopsony), which allows the payers to drive the reimbursement fees down, they also have a two-pronged resource advantage: attract Ivy-league MBAs to build sophisticated claim-processing protocols and discover every little pretext to deny or delay claim payment leverage the most powerful digital technology to implement those protocols on the ever-growing volume of claims. ClinicMind was founded to address two basic challenges facing providers: a patient-provider expectations mismatch and payer-provider adversity. First, the patients have transformed how they expect healthcare service delivery, but practice owners have not adapted their practice management methodology. Second, insurance payers underpay and delay payments because they make a substantial profit from the “float.” The float is the money insurers hold onto between the time they collect premiums and the time they pay out claims. In summary, 1. The Basic Mismatch Between Patients and Providers: a. Background: The healthcare industry has undergone significant changes in recent years, with patients becoming more proactive in managing their healthcare and demanding a different level of service. This transformation is largely due to increased access to health information through the Internet and the rise of patient-centered care models. However, many practice owners, particularly in traditional healthcare settings, have not adapted their practice management methodology to meet these changing patient expectations. b. Conflict: Patient Expectations: Patients today expect convenience, transparency, and a more personalized approach to healthcare. They want to schedule appointments online, access their medical records easily, and receive timely, clear communication from their healthcare providers. Provider Resistance: Many practice owners and healthcare providers are accustomed to traditional, paper-based methods and may hesitate to embrace digital technologies or change their established processes. This resistance can result from the comfort with the status quo, fear of the unknown, or high implementation costs. c. Resolution: To resolve this conflict, healthcare practices must adapt to the changing landscape. This may involve investing in electronic health records (EHR) systems, online appointment scheduling, telemedicine services, and more. Additionally, training staff and providers to use these technologies effectively is crucial. Clear communication with patients about these changes, the benefits they bring, and how data security and privacy are maintained can help build trust and reduce resistance. 2. Payer-Provider Adversity: a. Background: In the healthcare system, insurance payers (such as health insurance companies) often maintain a substantial portion of their profit through a financial mechanism called the “float.” The float is the money insurers hold onto between the time they collect premiums and the time they pay out claims. This float can represent a significant source of income for payers. However, it can create a conflict of interest with healthcare providers. b. Conflict: Payer Profit: Insurance payers benefit from maintaining a healthy float, as they can invest these funds and earn returns. The larger the float, the more profit they can potentially make. Payers have a significant advantage over the providers because of the oligopsony and because of significantly larger resources for better talent hiring and data processing. Provider Concerns: Healthcare providers, on the other hand, often face challenges in receiving timely and appropriate payments from payers. Delays or disputes in claims processing can impact their cash flow and ability to provide care. Providers feel that payers prioritize maintaining their float over ensuring prompt reimbursement. c. Resolution: Transparency and fair contracting: Establish clear and fair contracts between payers and providers that outline payment terms, including prompt payment schedules and dispute resolution mechanisms. Industry consolidation: Metcalf’s Law states that the value of a network is